Evidently fishing season opened this week. Fisher people of all stripes line my regular running trail and the funky smell of dead trout permeates the early morning air. That smell—muddy, scaly, wet—it takes me right back to childhood.

Fishing loomed large in my family. Everyone fished. For fun. For sport. On my dad’s side of the family, salmon fishing. Expeditions to Westport. Cases of canned smoked salmon and tales of my father seasick, green and puking. On my mother’s side of the family, trout fishing adventures. Long family vacations up endless gravel roads, hundred of miles into the Canadian wilderness to remote lakes filled with legendary trout.

I never got to go along on the Westport adventures, and truth be told, never wanted to. They sounded miserable. But the trout fishing expeditions? Everyone went along on these trips. We’d pile into our truck, the canopied back filled with our tent and sleeping bags, fishing rods, reels, creels, our green metal Coleman cooler, the green Coleman camp stove, jugs of kerosene. Dad drove while mom, Brucie, and I squeezed together on the bench seat. I generally straddled the gear shift while mom held my brother on her lap.

We didn’t have to go too far to meet up with my mother’s parents where my little brother and I defected for Grandma and Grandpa’s camper. We clambered immediately to the top bunk over the truck cab and rode the hundreds of miles up there, peering excitedly out the window, watching impatiently as the ribbons of graveled roads unfurled endlessly before us.

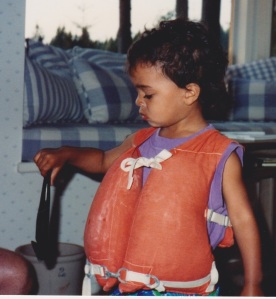

Behind the camper, Grandpa towed his boat—a silver and red aluminum craft, not fancy at all. Not large. I’m guessing 15 feet. It had one engine, maybe 10 horsepower and a set of oars. Bulky orange life vests, tackle boxes, recycled plastic containers filled with dirt and worms from Grandma’s worm farm, and gorgeous bamboo and cork fishing poles filled the boat.

I so wanted one of those fishing poles with the shiny and complicated reel. Instead, I had a child-sized fishing pole with an attached reel—a Zebco. A simple, plastic, one-piece uncomplicated piece of equipment. The Zebco reel was enclosed around the fishing line and had a button I pressed to release the line as I cast.

At the end of my line, a red and white bobber, a couple of lead weights, and a hook with a worm. At the end of Grandpa’s line? Shiny silver spoons, fancy lures, orange and pink and iridescent. Oh, how I wanted those lures on my line. I did not want my Zebco with its pedestrian bait and hook. I remember opening Grandpa’s tackle box and ogling his lures—so many options, each little tray and compartment filled with candy-like choices, fake gummy worms, fuzzy bumblebee bodies that hid barbed hooks.

My tackle box, yellow, held very little—a small glassine bag of hooks, some fishing line leads, those little brass clippy things that attached the lead to the rest of the fishing line. The spools of monofilament that squeaked when I pulled the line out. bobbers, lead weights. I remember pinching these little lead balls open with my teeth, putting them on the line, and then pinching them closed again—with my teeth (this cannot have been a good idea).

I caught a lot of trout on that little Zebco. I wound Grandma’s fat, coffee ground-fed worms onto those hooks, cast my line out, and watched that bobber with single-minded intensity. I sat in that boat, orange life vest tied tightly under my chin, bulky and smelling of last year’s fish, stained with the blood and slime that washed the bottom of the boat. I rarely ate the trout we caught, though I loved to fish. Loved the ritual, the waiting, the quiet on the water.

When we had caught our daily limit, I helped Dad and Grandpa clean the fish—I had my own knife and knew how to cut down the belly, how to use my thumb to scrape the innards out. I can still feel the trout’s spine under my fingers, the serration against my thumbnail.

As I got older, I lost my desire to put the bait on the hook, to slice open the fish, to scrape out the guts. Squeamishness replaced my attraction to the ritual, and I don’t think I ever took my children fishing (though my dad, their grandpa did). This realization as I ran my laps around the lake this morning made me sad. Fishing filled my early years—that Zebco rod and reel saw me through fishing derbies, represented independence (my brother and I used to camp by a stream near our house, fish and cook the trout we caught for dinner over an open campfire), and connected me to family in ways nothing else really did.

I smiled as I ran this morning to see all of the children with their parents, and grandparents lined up around the lake, building memories, casting their lines, grinning widely as they held their catches. If I ever have grandchildren, we will go fishing. They will have a Zebco.