Many years ago, flummoxed by the joys and perils of raising two non-white children in our predominantly white culture, I wrote an essay expressing my doubts and fears, and (surprising to me now) my certainties (you will recognize them when you see them). Some of what I wrote makes sense and some of it clearly needs rethinking. Yesterday on the day we celebrate Martin Luther King, Jr., my eldest daughter, now 23, texted me (this is how we communicate these days). She was wondering if I thought it odd that the company for which she now works didn’t celebrate the national holiday. I do find it odd, odd that only governments and banks shut down on this Monday when the world grinds to a halt, more or less, for other national holidays: Christmas, Thanksgiving, Memorial Day, the 4th of July.

My initial response to her was yes, MLK day is like Veterans’ Day or Presidents’ Day—national holidays that go unobserved by most businesses in the name of productivity and profit. She replied that businesses should do more to honor a man who inspired the policies so many companies tout when they brag about being diverse and multicultural. I agreed.

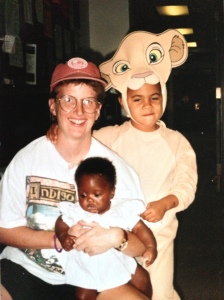

I dug up that essay and I emailed it to my daughter yesterday. We had an enlightening and informative (for me at least—I can’t speak for her) email exchange about White Privilege after she read this. She asked if I’d ever blogged about the subject. I haven’t. I’ve been fairly quiet about it over the years. Why? Fear. Fear of offending someone, fear that I didn’t know enough about the “issues,” that I hadn’t read enough, studied enough, experienced enough. I thought overnight about this fear and I’ve decided that if someone is offended by me writing about my experience, then they are missing my point. I also decided I haven’t talked or written enough about race, in spite of the fact that I helped raise two African-American children. (Point of clarification—Anna, my eldest is mixed race—Native American, African-American, white; Taylor is African-American). Maybe it’s not too late. So, I am posting my long ago essay publicly for the first time—I’ve revised it some for clarity but mostly this is as I wrote it 18 years ago. Here it is:

Last week my daughter’s preschool teacher asked me if I’d talked with her about discrimination. I haven’t. But I’ve been thinking about it a lot lately. What do you call the adopted multiracial child of white lesbians? I don’t know, but I’m sure as the years pass us by we’ll learn more than we care to know. I told the teacher that our family had discussed variations in skin color and the many other ways in which people are different and alike. How to explain discrimination based on skin color to a five-year old?

Our oldest daughter carries an acute awareness of her skin color. She knows that her skin is much darker than ours. She also knows that her little sister’s skin is darker than her own. “I have browner skin than you, but Taylor has the darkest skin, right?” She’s been known to ask this question on more than one occasion. And when we brought her baby sister home, Anna unwrapped her, peered beneath the baby blanket and with some relief announced, “Oh good, she has brown skin, just like me.” She knows which kids in her daycare have brown skin, though ethnicity is an elusive concept. For her, the world is comprised of people with varying shades of brown skin—from very dark brown (like her sister) to not brown at all except for little brown spots (freckled, like mine)—and people with porcelain white skin and long blonde hair.

I had no idea how deeply children internalize societal messages until we began dealing with what, in our house, has become “the hair thing.” Anna’s hair is a crop of silky brown ringlets, which we have, until recently, kept short for the sake of simplicity. Imagine my surprise when, after we agreed to let her grow it out, she expressed her delight at the prospect of finally having straight hair. She was shocked to learn that her hair might grow long, it would not grow straight.

I’ve read The Bluest Eye. I know the world bombards our children with images of white babies, white Barbie Dolls, white Make Up Beauty dolls, and I know that I too eagerly try to overcompensate at times, for this deluge. This year for the first time, Anna knew early and consistently what she wanted for Christmas: a pogo stick, a computer, and a Makeup Beauty Doll (which really is just a head with hair). Being the sensitive, aware, and hip parents that we are, we bought her the African-American version of Makeup Beauty, basically the white doll painted brown with straight brown hair instead of straight blonde hair. These details were not lost on Anna. Her face lit up as Santa handed her a box just the right shape for the coveted Makeup Beauty, but the excitement faded quickly into disappointment when she pulled the brown doll from the box. Anna suffers our political correctness with a sigh and a roll of her eyes, but she knows that Makeup Beauty is supposed to be white. After all, she told us, the make up only shows up on white skin. She has a veritable rainbow selection of Barbies residing with her African-American Cabbage Patch Doll, her Black Raggedy Ann and Andy dolls, but she only plays with the white ones.

So, how do we talk with her about discrimination? There’s color awareness, and there is discrimination or prejudice based on difference. How does the five-year-old mind wrap itself around that one? Is Anna being excluded at school because of her skin color? Are teachers, parents, workers excluding her or making decisions based on stereotypes? Anna’s teacher gave me a book for kids about discrimination, Black Like Kyra, White Like Me, that is full of stereotypes. Kyra lives in a violent section of the city. She meets her white friend at the Youth Center. To escape the violence, Kyra’s parents move to a predominantly white section of town and encounter nothing but resistance, violence, and harassment. The message, it seems, is that people of color live in places that need escaping from, but the white people don’t exactly roll out the welcome wagon in the desirable neighborhoods. And I should share this information with my five-year old? Where is the line between preparing a child to meet challenges and adversity and raising a child to expect conflict and harassment?

Right or wrong, the one feature by which my children will always be judged in this country is their skin color. Before strangers know Anna and Taylor have two moms, before anyone knows their socioeconomic status, their spiritual convictions, their occupations, my children will be judged as other than white. The content of their characters will come later. The question is, do I teach them to expect this judgment as inevitable? Do I read them books in which people of color are run out of white neighborhoods? Do I tell them that one day they may not be invited over to play at a friend’s house because they are African-American, Native American, multi-racial, obviously different?

Or do I teach them about respect, about the value of difference and diversity, about some people’s narrow mindedness. Do I teach them to expect acceptance if that is what they offer? And if I teach them these things, what will I say the first time one of them encounters a racial slur or rejection simply because of their skin color? A great gulf exists between my experiences and what my children will encounter. I cannot be naïve and pretend it won’t happen, because it already has. I expect discrimination and prejudice will continue to find their ways into our lives in more potent measure than they have thus far.